CitiCAP Journal 6

Executive Summary

The CitiCAP project (Citizens’ cap-and-trade co-created) received funding from the EU UIA 2nd Call, Urban Mobility theme (2018-2020). The project concentrates on enabling and promoting sustainable urban mobility in Lahti.

Among other measures, such as an open mobility data platform and Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP), the project has developed a model for personal carbon trading (PCT) scheme on mobility and an application for the citizens that enables real-time tracking and visualization of one’s mobility carbon footprint.

The mobility data platform opens up possibilities for new mobility service development. CitiCAP has also developed a model for designing the bicycle route network, by building a 2,5 km smart bicycle highway that includes the latest technical solutions to offer smooth and direct routes from the residential area to the city centre all year round.

This final journal provides a summary of the main deliverables achieved by the project and how their delivery evolved over their lifetime. Annex A covers this in more detail, in relation to the operational challenges associated with all UIA projects as reported in previous Journals (1 to 6). It shows the evolution of the project at different implementation stages reported in each Journal and the interconnection of actions and decisions taken in order to achieve the final project outcomes.

The final section of the report concludes with my four final takeaways and lessons learned from the project.

Lahti Direction - Approval of the SUMP

The Lahti Direction is an open participatory process which sets out the city framework and long-term strategy for the city to ensure a sustainable and healthy life for the citizens. The Lahti Direction work is done in cycles of four years by the City Council terms. In 2017, Lahti started the process that integrates Master Plan and SUMP, the latter being drafted for the first time through CitiCAP[1]. By linking the long-term strategy for the future development of the urban area, alongside the future development of transport and mobility infrastructure and services, it can greatly influence lifestyle and mobility behaviour. This is because safer streets encourage walking and cycling and convenient access to public transport makes it easier to use. In broadest terms, they encourage dense, more connected cities which enhance sustainable mobility choices (as envisaged by CitiCAP) because the conditions support these modes of transport[2].

The European Commission has long extolled the benefits of implementing SUMPs and has detailed guidance to support implementing such plans in cities across Europe and in other global regions. The Commission’s guidance[3] was used as the template for Lahti’s plan towards more sustainable forms of mobility. The final plan - which was approved in January 2021 and follows council terms, in that it enables continuous monitoring of continuous development work and implementation of measures along this political cycle. The objective of the SUMP has been designed to go beyond sustainable mobility but has taken a broader tone, so that it contributes to the achievement of the Lahti Carbon Neutrality Target 2025 and the 2030 mobility mix objectives (more than 50% of all trips will be made using sustainable modes of transport). The main elements of the plan are presented below in figure 1.

Figure 1 - List of Lahti’s SUMP Measurers (Lahti SUMP, 2021[4])

The SUMP is centred around four key elements, each containing a number of different actions that will be implemented over the source of the SUMP’s lifespan. Annex B provides further details on the individual measures, period of implementation and desired end results. It is not possible to report stakeholder feedback on the measures taken as they were only finalised and agreed at the start of the year. Rather, the purpose of this Journal is to provide the reader with a breakdown of these approved actions, as it addresses the question that CitiCAP sought to solve: what is the future of mobility in Lahti for the years ahead? Lahti’s new SUMP has the answer.

A Smart Bicycle Highway that has improved cycling conditions in Lahti

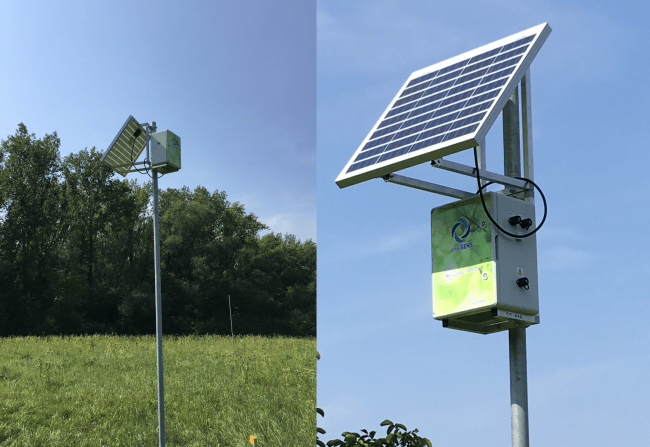

The main infrastructure development of the CitiCAP project was the 2.5-kilometer-long bicycle highway from the Lahti Travel Centre to Ajokatu (figure 2). The purpose of the bicycle highway is to enable smooth and safe year-round cycling, with its cycle path clearly separated from other transport modes that simultaneously improves walking conditions, notably by employing smart technologies. When reaching Ajokatu, the cycle path connects with another new bike path from Renkomäki to Uudenmaankatu Street and now forms part of a cycling network plan within the city’s master planning work, consisting of about 40 km of main routes and district routes. In total, around €1.6 million euros was earmarked for this section of the UIA CitiCAP project with citizens heavily involved in the planning of the route through workshops. The innovative element of the project lies in the fact that the bike path has experimented with various smart solutions. The project has also used recycled and / or recyclable materials in the construction of the highway as much as possible, thereby helping to advance circular economy efforts of the city.

The bike path received a lot of local attention during its early consultation phase which also encouraged the city to test a range of smart solutions that citizens felt would add value to cyclists, such as information screens, smart bicycle racks and smart lightning, and the route has been diligently paved with social media columns, for example. About 7% of the total bike path budget was spent on smart features.

Figure 2 - CitiCAP Apilakatu-Matkakeskus smart bike route

Other innovative features that have been installed include sensors that provide real time information on public transport data to enable seamless interconnected journeys along with ‘encouraging’ personalised messages on information tables. Other new solutions include energy-efficient adaptive LED lighting which reacts to movement and dim and brighten as needed and according to the users. Road signs are also projected on the street, for their part, can be seen in the dark, rain and blizzards.

Displays are still being installed on the bicycle highway, which will be used to indicate the number of users of the path and, for example, weather information. Sophisticated winter maintenance will also help to keep the cycle lanes accessible throughout the year. A technique based on snow brushes has been piloted in Lahti in previous years, and a total of 20 kilometres of cycle lanes are due to be brushed this winter. Importantly, the new CitiCAP network will give the city a testing platform that will allow the trialling of new techniques and smart solutions for years to come, and the city is already preparing for these kinds of experiments by installing the necessary infrastructure and cabling for future initiatives.

Thanks to this project, Lahti now has a lot of potential for becoming a thriving cycling city and through better infrastructure - as provided by the CitiCAP bicycle highway - it can help to lay the foundation for a positive reform of the cycling network and changes in behaviour for years to come.

Lessons Learned from CitiCAP’s PCT Pilot

Prior to CitiCAP, PCT has been a relatively untried policy, especially in the transport sector (see CitiCAP Zoom-In 1 for further information[1]). In its purest form, individuals are allocated an allowance of carbon from within an overall national or local cap on the quantity of carbon emissions produced by individuals within the jurisdiction. People surrender their credits as they make certain purchases that result in emissions. Those who need or want to emit more than their allowance have to ‘buy’ allowances from those who can emit less than their allowance. Alternatively, those who emit less can be rewarded for doing so. The market effect encourages people to pursue energy efficiency and to reduce their carbon emissions. Over time, the overall emissions cap (and therefore individual allocations) can be reduced in line with international, national or local targets. As a result, the price of carbon allowances becomes more expensive encouraging people to reduce their emissions.

Thanks to the CitiCAP project, Lahti has become the first city in the world to launch a PCT to reduce emissions from transport. Lahti’s approach differs slightly to that described above in that it is primarily an incentive system that encourages users to reduce their mobility emissions via 1) financial incentives through CO2 pricing; 2) providing information on users’ emission and their reduction possibilities; and 3) proving an online marketplace to reward citizens[2]. The model adopted in Lahti is simpler in that it does not utilise a market mechanism that would enable participants to trade emissions between themselves. As such, Lahti’s PCT model is a voluntary-based one that emphasizes incentives over penalties.

The pilot and research part of the project started in June 2020 until the end of 2020. The initial goal was to have around 1,300 users in the pilot, which equates to around 1% of the population of Lahti. In the end, approximately 2,500 were registered in the application, which exceeded the original target. In addition, approximately 150 users participated in a reference group where mobility was recorded but who did not take part in PCT. Based on the data and analysis done to date, it has shown that the PCT system has worked as planned: user specific emission allowances were allocated based on initial background questionnaires, participants’ mobility modes and distances were automatically recognized, and information on mobility emissions was provided almost in real time.

The number of active users of the CitiCAP application during the PCT pilot varied weekly from 100 to 350. The average recorded number of trip distances, by mode, during the pilot phase (24 February 2020 - 24 December 2020) shows that car travel was the dominant mode of transport (circa. 80-90% mode share), especially for longer distances. Between the end of July to end December 2020, emissions fell by around 40% (see figure 3) but it is not clear whether the PCT scheme alone was responsible for this, even though 36% of users stated that their mobility choices became more sustainable due to the use of the application. What is more likely, is the impact of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions when they came into force over this period. Data shows that the mobility of Lahti residents decreased by up to half and the use of public transport decreased by up to 80% as people stayed in to remote work and school.

Figure 3 - Emissions level of PCT participants and allowance price changes during the Autumn of 2020 (source: CitiCAP[3])

When looking at emissions over this period, the allowance prices reached a peak of just over €0.75per kg of CO2. This price high saw a gradual reduction in emissions but not a marked reduction as hoped. People surveyed did not really register this price rise (only 37% of participants did) and as a consequence, it had very little impact on user’s average weekly emissions. It can be taken from this that the economic incentive of the scheme was not great enough alone to influence behaviour (only around 175 vouchers were redeemed during the test and pilot phases). Rather, the desire to change has perhaps a stronger influence in terms of reducing an individual's mobility habits than a CO2 price but that the PCT scheme was an important mechanism to engage people to enact this willingness to change. What the results do show for certain is that it is possible to implement a voluntary PCT scheme using ICT technology.

[1] https://www.uia-initiative.eu/sites/default/files/2019-03/Lahti%20Zoom-In%201%20PCT_0.pdf

[2] MOTIVATING CITIZENS TO REDUCE THEIR MOBILITY EMISSIONS THROUGH PERSONAL CARBON TRADING (CitiCAP Final Conference, 2021): https://www.lahti.fi/en/files/citicap-pct-pilot-and-main-results/

Conclusions & Final Takeaways

My interest in the Lahti project, notably the PCT part of it, stems from my time working at the UK Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in 2008 where we assessed the feasibility of implementing such a scheme. The conclusion was that it was a policy idea that was 'ahead of its time' due to high implementation costs and public resistance to the concept[1] but I have always wondered whether it would be taken up as a policy option in the future. This in part explains why I was so excited by and enjoyed working on CitiCAP.

These past few years have had their obvious challenges, but the city should be rightly proud of what it has achieved. Coming to the end of this journey, I would like to share with you my four final conclusions and takeaways as the UIA Expert for the CitiCAP Project.

1. CitiCAP has the potential to be scaled up in Lahti and beyond

CitiCAP got a lot of positive attention, both EU - and internationally. It was awarded the Gitex 2019 Smart City series (biggest technology exhibition in the Middle East) and its global climate action plan was rewarded with the 2021 EU Green Capital Award. I think that the interest in CitiCAP lies in the fact that it presents a new policy approach to dealing with emissions from a sector that is difficult to abate but one that has received strong, long term citizen support.

There is clear interest in other cities to build on the Lahti experience, so it is important that the lessons learned from CitiCAP are shared widely. For me, the most endearing insight from the project is how the trips or days out accrued through the PCT’s marketplace leads to experiences and happy memories with friends or families for individuals. It’s a policy approach that personalises in a positive way (unlike, say, a parking fine) and that enables people to reflect on their lives as a whole and consider future generations. Rarely does a government policy do that, which I feel is the real game changer and as a consequence, has the potential to be scaled up both regionally and globally.

2. CitiCAP has demonstrated that PCT is a viable policy option to influence positive behaviours

I reported in Journal 5 that during the test phase of the scheme, around 60% of users easily understood the purpose of the PCT and around half found the PCT as an interesting policy development. The final results reflected in this Journal show that the scheme is an effective and engaging way to encourage people to register and reduce transport emissions. Given the willingness of citizens to participate and to continue with the project, it shows that there is no barrier to local Governments developing and deploying policies that will prepare the ground for personal carbon trading in the future.

3. CitiCAP has not just engaged it citizens, it co-created a future with them

Active participation of stakeholders was always essential to the success of the project so that citizens understood their role and place to help foster a culture of co-creation in all its city policies. Co-creation is a powerful concept: engaging broad stakeholders in a design or problem-solving process as co-designers. In fact, participatory design was born in the region and as such, it is fitting that co-creation features so prominently in the CitiCAP project - especially as the UIA is all about testing new and unproven solutions to addressing urban challenges. The project has shown that all stakeholders (and this also means that the citizen and city does not exist alone) have an important voice, which has been best reflected in shaping the Master Plan / SUMP process, so that they get to understand each other's perspectives, possibilities and constraints. In doing so, it has created joint ownership of CitiCAP and its outputs, which marks a crucial point in the city's transition to cleaner and better urban transport in the future.

4. While Covid has had a major impact on our daily lives it could help encourage the uptake of sustainable transport going ahead

We all know that Covid has impacted our daily lives, meaning that we were either travelling less or walking and cycling more. I would argue, this makes CitiCAP and its main deliverables a more attractive policy option for decision makers in that it helps lay the foundations for positive changes to transport behaviours that may result in permanent habitual changes. Research has shown that disruptions can be a catalyst towards this shift but avoiding negative consequences, this requires governments to take decisive actions sooner rather than later. With Covid, many cities have rediscovered the benefits of cycling and walking and CitiCAP can help to reinforce this trend in behaviour, as it had laid the necessary infrastructure and long-term planning for this to happen. This can be the lasting legacy of CitiCAP.

[1] UK Government Environmental Audit Committee (2008): https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmenvaud/565/565.pdf